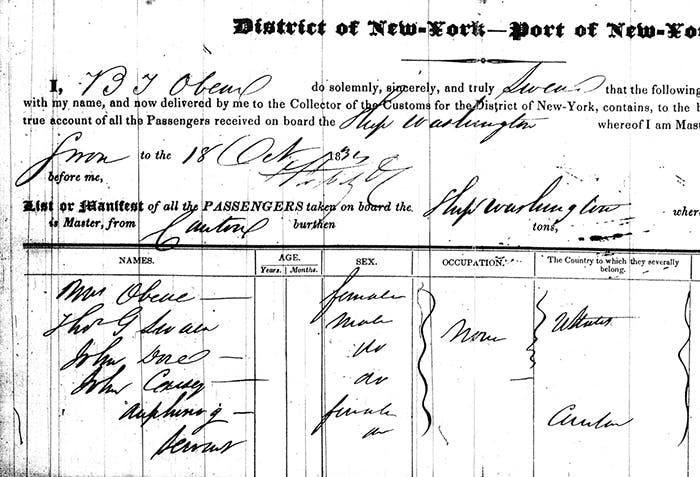

Through the Carnes Brothers, who were merchants who used Afong Moy to advertise Chinese goods, Moy made her way to New York City in 1834. She sailed from Guangzhou, China, surviving on terrible food and potentially fatal weather, and became the first Chinese woman ever documented in the United States. Although Moy's family was probably middle class and had enough money for foot binding, it's possible that they were having financial difficulties as a result of famine. Moy would spend at least 17 years in the United States, and it's possible that the brothers compensated her family for her role.

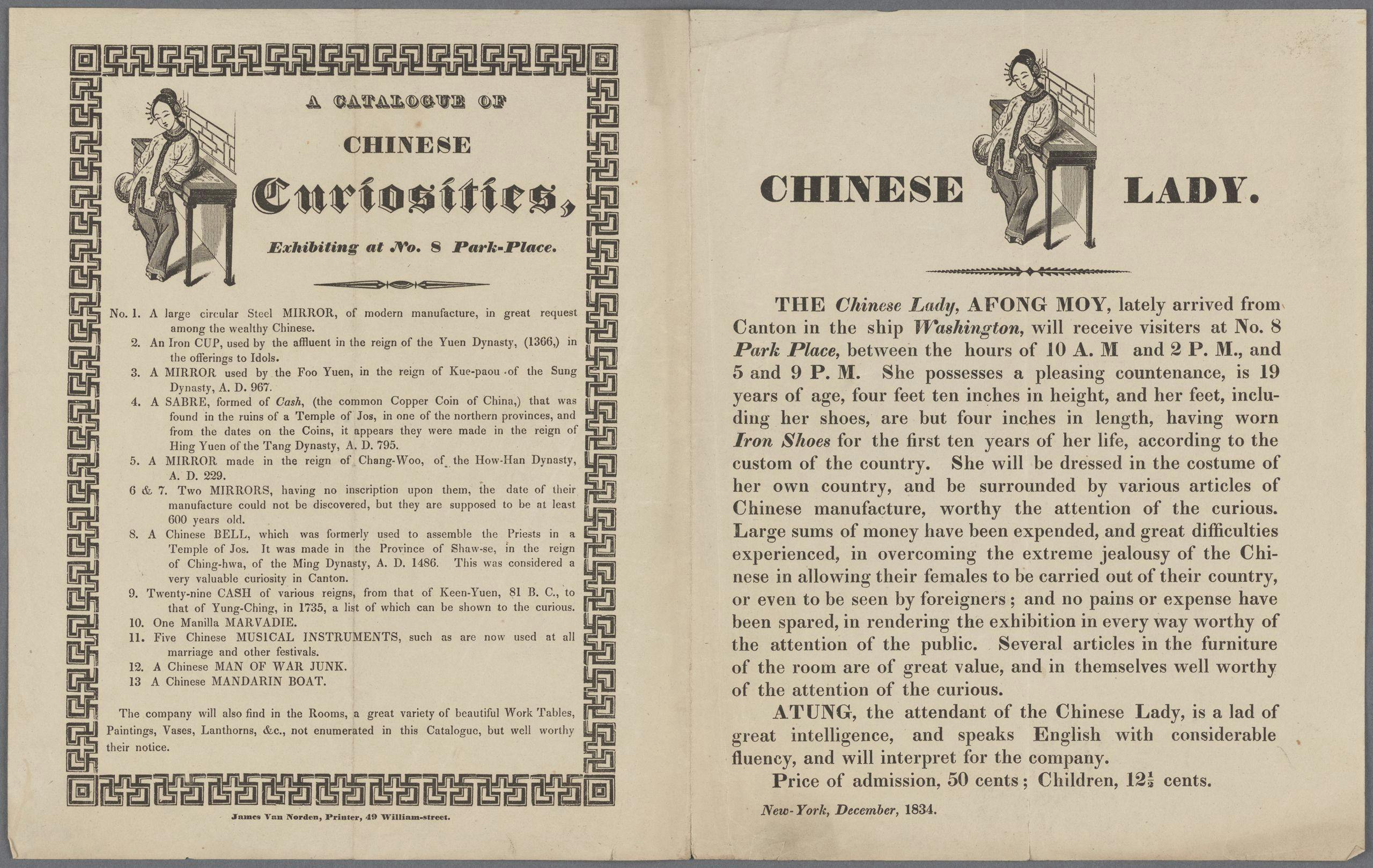

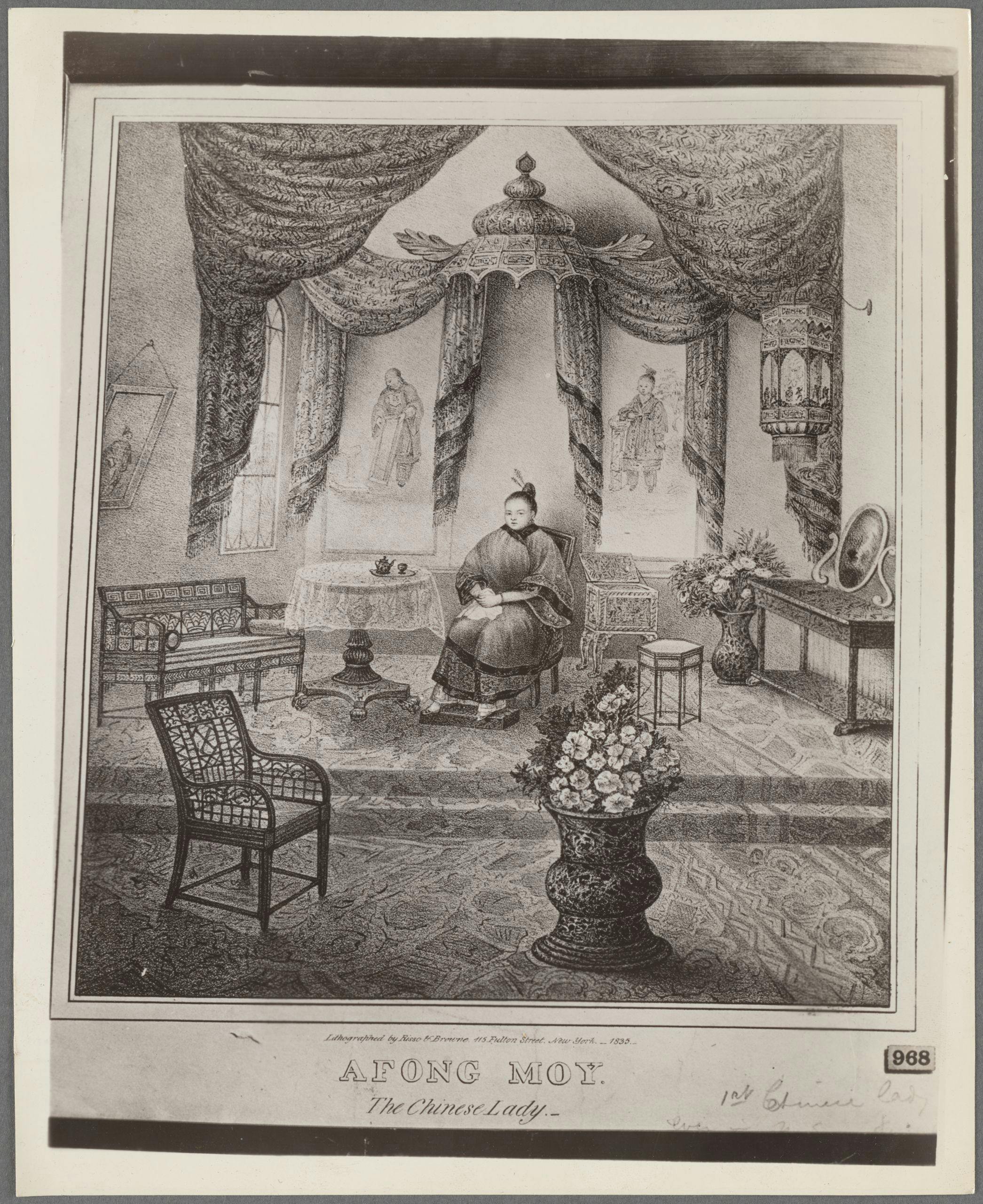

Her public appearances had a significant impact on Americans' perceptions of China. Moy gave spectators their first glimpse of a Chinese woman by being marketed as an exotic rarity and making appearances in constructed settings filled with "Oriental" items. She encountered well-known people like President Andrew Jackson as well as regular spectators. Although Moy herself left no written history, the materials surrounding her performances such as broadsides, newspapers, and visitor diaries helped strengthen early American perceptions of China to be mysterious and exotic, shaped more by novelty than by firsthand experience.

Afong Moy endured dehumanization and exploitation during her stay in America, despite her public presence. She was treated more like an object than a person when her exhibition was on tour in January 1835 and on display in a museum in Philadelphia. She had to allow eight white physicians to examine her bound feet while she was there, which was undoubtedly against Chinese traditions and her right to privacy. The cultural significance of foot binding was not well understood by the American audiences who came to see her. Instead, they responded with astonishment and fascination, seeing her small feet as proof that Chinese culture was bizarre or inferior and that she was somehow less than human.